Introduction

Free Voluntary Reading (FVR) is a language learning practice in which students choose what they read from a selection of texts in the target language that are interesting and level-appropriate. It is a powerful, research-supported practice that promotes language acquisition through meaningful exposure to the target language and fits naturally within an acquisition-driven world language curriculum. Rather than focusing on explicit teaching of rules or isolated skills, FVR provides learners with ongoing, meaningful input that naturally supports language development. As a result, students experience steady growth in proficiency while developing a more positive relationship with the language and with the act of reading.

What Free Voluntary Reading Looks Like in World Language Classrooms

In practice, FVR is relatively simple. Students choose a level-appropriate text to read silently and independently, often from a classroom library that includes leveled texts and readers for beginners as well as more advanced options. Due to how beneficial reading is to language acquisition, some teachers treat FVR time as a “sacred practice” and will not issue students passes to leave class during reading time. During FVR, the teacher often models expected behavior by reading along with the class. On occasion, the teacher may conference with students about what they are reading. One FVR time is over, the teacher may either lead a discussion about the books the class is reading or move on to a different lesson.

FVR is also flexible. The amount of time students read may vary from five to fifteen minutes at any point during the class period. In addition, FVR may take place every day or only on certain days of the week. Consistency of FVR matters more than the length of time. In addition, FVR naturally allows for differentiation. Strong students will be able to read more challenging texts while novice learners can build confidence and comprehension by selecting readers for beginners that provide the support they need.

Principles of Free Voluntary Reading

Three principles define FVR. First, student choice is paramount. Learners themselves select texts to read that genuinely interest them, and they have the opportunity to abandon a text if they lose interest in it. Second, the texts are comprehensible, meaning students can understand most of what they read without constant translation or teacher intervention. Many readers for beginners designed for FVR include a comprehensive glossary to facilitate this. Finally, FVR does not have forced accountability. This means that there are no required worksheets, quizzes, or tests attached to the reading. This allows FVR to be a low-pressure and hopefully pleasurable activity rather than a task to be completed for a grade.

The Research Behind Free Voluntary Reading

Free Voluntary Reading is strongly supported by second language acquisition research. Scholars such as Stephen Krashen, the researcher who developed the Input Hypothesis, have long emphasized reading as a critical source of comprehensible input, which is necessary for language acquisition to occur. In The Power of Reading, Krashen states that consistent reading leads to better reading comprehension, writing style, vocabulary, spelling, and syntax because students are exposed to vocabulary, grammar, and language structures repeatedly and naturally.

Just as importantly, FVR fosters positive attitudes toward reading. Students who read by choice are more likely to see reading as enjoyable rather than intimidating, which increases the likelihood that they will continue reading independently.

Teachers interested in exploring research about FVR can reference this article by Stephen Krashen, who reviewed over 100 studies about FVR and compiled a list of takeaways about it based on these studies.

Getting Started with Free Voluntary Reading in the World Language Classroom

In his book Pleasure Reading in the World Language Classroom, author Mike Peto says that teachers should wait to institute an FVR program until after students have had a lot of exposure to high-frequency vocabulary (teachers can find lists of the highest-frequency words in their target language here), with special emphasis on the Super 7 and Sweet Sixteen Verbs (you can find resources for teaching these verbs in French and Spanish here). This foundational vocabulary naturally appears in classroom interactions and should not require a separate curriculum. Instead, once students have sufficient exposure, FVR can become an integral component of a proficiency-oriented world language curriculum.

Most teachers wait to institute FVR at the beginning of the second year of a middle school world language program or the second semester of a first-year high school class. In addition, most teachers recognize that students need to build up the stamina needed to read in the target language; they start with a small increment of time like five minutes and then slowly add minutes over time as students get used to the routines and expectations of FVR (Check out the expectations slide from this blog with student expectations that this teacher projects during FVR). Several short, frequent reading sessions throughout the week are better than one or two longer sessions.

Building an FVR Library

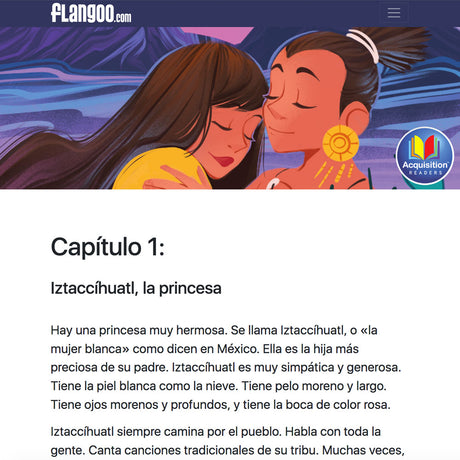

An effective FVR library should include a wide range of both fiction and nonfiction texts. While some authentic resources may be included, many are not accessible to novice learners, making readers for beginners an essential part of any FVR collection. A strong library can include leveled readers, newspapers, hard cover children’s books, collections of infographics, ebooks, and illustrated class-created texts. Variety is key, as students’ interests and proficiency levels vary widely.

Teachers looking to start an FVR library do not need to create a complete and comprehensive library all at once. It is perfectly acceptable to start small with only a small number of readers and gradually add titles over time. Teachers worried about financial implications of FVR might want to augment their collection with illustrated copies of texts from class or free stories from the Internet (teachers might want to explore this site, which groups stories by proficiency level in multiple languages, for printable stories) as they slowly add more readers to their library.

Addressing Common Concerns about FVR

Teachers often worry that students will not actually read during FVR if it is not graded, especially in classrooms where students are accustomed to earning points for every task. This can be mitigated in a number of ways. Teachers may talk to the class about the many benefits of FVR and how it enhances language development to increase buy-in. Some teachers may use a rubric to assess student habits during FVR (Mike Peto's book Pleasure Reading in the World Language Classroom has a copy of an effective Habits of FVR rubric). Other teachers ask students to talk about what they are reading, either privately or in a group. This holds students accountable as they quickly realize how hard it is to fake it when they are asked to talk naturally about a book. The desire not to embarrass themselves may be the motivation they need to take the activity seriously. Other teachers just wait and give students time to get adjusted, improve their reading stamina, gain confidence in their reading abilities, and become cognizant of their own progress over time, which is intrinsically motivating.

Time is another common concern. While Free Voluntary Reading does require dedicated class time, implementing FVR is a matter of strategic substitution rather than curricular addition. For example, by utilizing FVR at the beginning of a class, educators thus eliminate the need to prepare daily warm-up activities. Including an FVR block in a plan also takes some of the stress out of preparing sub plans. And ultimately, FVR serves as a time-efficient intervention; by fostering organic language growth, it minimizes the future need for remediation as it simultaneously accelerates overall student proficiency.

Conclusion

Free Voluntary Reading supports language acquisition by giving students consistent, meaningful exposure to the target language in an enjoyable context. As a student-centered and sustainable practice, FVR strengthens both proficiency and confidence while supporting long-term language learning goals. When embedded thoughtfully into a world language curriculum, FVR becomes a powerful foundation for lasting language growth.